Racing Icon,

Carroll Shelby's

Return to Drag Racing

by Susan Wade

4/8/04

Carroll Shelby is best known for his triumphs as an owner/driver in sports car, Indy, and other auto racing disciplines. However, he had a brief stint in the 1967 drag racing season, where he made a significant impact. As anyone in the sport knows, a Shelby Ford Cobra is one of the most powerful and now valuable sports cars ever produced. The "Shelby" does not stand for folk singer Shelby Flint. While originally the Cobra roadster first appeared with a 289-cid engine, it was the 427-cid version that was the heart stopper and the one in original today that can be worth well over a quarter of a million dollars per copy.

Naturally, a gun that big impressed drag racers and it wasn't too far into the season that they showed albeit in limited numbers. The most famous of the proponents was NHRA 1989 Funny Car champion Bruce Larson. Larson and Jim Costilow's Ford set two NHRA sports car records and one class win at the 1967 NHRA Springnationals at Bristol, Tenn.

Incidentally, at that same race, Shelby enjoyed bigger success and that came in Top Fuel. Shelby was a big backer and promoter of the Ford SOHC 427 that really ruled the sport that season. Connie Kalitta drove a "cammer" to the title at the '67 NHRA Winternationals, and at Bristol, Don Prudhomme wheeled the "Shelby Super Snake" fueler to a win over the late Pete Robinson in NHRA's only all-Ford Top Fuel final.

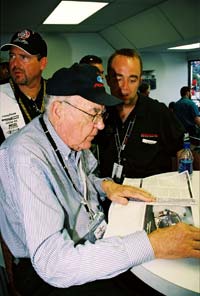

Shelby was and has been a pro-drag racing force since those days. Leaving aside his racing accomplishments, he counts people ranging from Wally and Barbara Parks to Linda Vaughn to John Force as good friends. He most recently visited the 2004 NHRA Gatornationals and discussed his past, present and future.

For less than a minute their worlds collided.

And to a casual observer, Carroll Shelby, for decades the toast of the Burgundy-and-brie road racing set had little in common with the wildly popular National Hot Rod Association Funny Car driver John Force. It might have seemed like a courtesy call for Ford-entrenched Force to dash into the tower and shake hands with the man who's one of the automotive industry's most celebrated innovators ... a respect-your-elders gesture.

But Shelby, perhaps best known for his development of the Cobra and the Mustang, has a kinship with modern drag racing's most charismatic character.

Shelby, 80, has a softer spring in his gait these days and a teasingly naughty sense of humor that's almost as subtle as his pudding-soft Texas accent. But when he visited the Mac Tools Gatornationals that Saturday afternoon fresh from serving as grand marshal for the 12 Hours of Sebring, any educated racing fan could see the magnetic pull.

Shelby's career, which included driving, designing and manufacturing, began at a drag strip in Dallas. Although he quickly switched to road racing and made his mark at Le Mans after retiring from the cockpit, and collaborated with each of America's "Big Three" manufacturers, Shelby is cut from the same cloth as Force.

Both know the struggles: first to achieve a level of accomplishment, then to maintain it. Neither is pretentious, for neither started with a pile of cash. They tasted failure long before success, but they remained true to their visions.

Force lived in a rickety trailer in California's non-90210 zip codes with his parents, two brothers and a sister -- and had to wait until his parents were finished watching TV for the night before he could go to sleep on the pull-out couch bed. When he stepped out on his own, he lived in his car parked in brother Walker's driveway and survived on hard-boiled eggs and diet cola, preferring to spend what little money he made on his racing venture, one which Walker was convinced was so unsafe it would kill him. He slogged through nearly 70 races in nearly 10 years before he won the first of his NHRA record 109 trophies.

Shelby ditched his Dallas dump truck business in the late 1940s and took up raising chickens. His first batch of broilers made him a $5,000 profit -- no chicken feed by 1949 standards -- but he declared bankruptcy when his second group of chickens died from Limberneck disease. "I'd been a chicken farmer. All my chickens died," Shelby said. "I was looking for something else to do. And I decided I'd always loved cars. So I tried to see if I could make it as a professional racing driver. And three years later I was driving for the factories in Europe."

Shelby, like Force, knows how it feels to hear people laugh and not know whether it's with you or at you. But both have used that to their advantage as marketing tools. Force is legendary for his rambling but entertaining monologues. His trademark sooty fire suit, though, is no match for Shelby's early racing attire. One day in August 1953, Shelby realized that he didn't have time to change clothes before heading to the track. So he wore his striped bib overalls, splattered with flecks of chicken manure. He credits colorful Texas sports editor Blackie Sherrod with putting his picture in the newspaper because of his unique sense of fashion.

(Then again, Shelby always had gone by instinct and done things his unique way. When he was an Air Force pilot during World War II and flew training missions out of Lackland Air Force Base near San Antonio, he would correspond with fiancée Jeanne Fields by sneaking love letters into his flying boots, then once he was up in the air, dropping his missives onto her family's farm on flyovers. It won the girl -- they were married in December 1943.)

Shelby also won in his first attempt behind the wheel, driving a hot rod with a flathead Ford V8 in January 1952. And that May, he had traveled up to Norman, Okla., for his first road race and driven his MG-TC to victory against other MGs. That same day, against stiffer competition from Jaguar XK 120s, he won again. Soon after, he won an early SCCA event on a road-racing course set up near tiny Cadd Mills, Texas, driving a Cad-Allard. So he was building a winning reputation. But people couldn't look past his clothing.

And so, as Shelby sat in the air-conditioned tower at Gainesville Raceway -- a luxury he earned by his own achievements and not some corporate canonization -- he clearly was not done analyzing. This was his first visit to a drag race outside of Pomona, Calif., and the West Coast in nearly 20 years. He squinted his pale blue eyes slightly, not because his vision was poor. Instead, he was sizing up the considerable crowd, one of the best in recent times at the Gatornationals, and enjoying the energy.

"Look at these kids, sitting out in the sun all day long," he said. "Never move. Hell, they even hate to go to the bathroom." He smiled a satisfied smile, as if to say that in this day of computers, hand-held computer games, cell phones, CD players, and various other technological distractions, he was pleased that motorsports still could command the attention of busy and choice-riddled America. On a gloriously hot spring day, no less, these fans ignored the media's college-basketball over hype and chose to spend a full day at the drag races, on metal bleachers, even though nitro-class drivers were having a hard time hooking up with the track and regrettably not giving them their best show. For Shelby, it was reassurance. He knew the show -- his show, motorsports, still had that appeal.

And he attributed much of that to John Force, whom he considers much more than the driver of the Castrol Ford Mustang Funny Car or the owner of three Mustangs in the class. He said he regards Force as the glue that holds NHRA together.

"Force makes this sport with all his bullshit," Shelby said approvingly. Shelby also visited in the Gainesville Raceway suite with Don "The Snake" Prudhomme, a relentless, cutting-edge driver he sponsored back in the day, and called him "a class act," adding, "I just think the world of him." But he said of Force. "He's really a class guy, too. This sport's really a hell of a lot better off because of him. But it's not bullcrap, really. You think he's just carrying on like an idiot. And it all makes sense. He's a wonderful spokesman for the sport. He's one of the reasons it's growing as fast as it is."

The Sport Compact Series has intrigued Shelby. And because he has made his mark by thinking globally, he doesn't see a threat to the domestic market. "Drag racing is what a lot of them can afford to get into," he said of the young racers today. "You know we're here for big-time today, but these little pocket rockets, they get 100,000 people out there at Palmdale (Calif.) on Friday and Saturday for these kids to run those little front-wheel-drive cars. They're running 175 miles an hour in the quarter-mile. You think of the technology that it takes for these kids to take a gearbox that's built for 100 horsepower and take one of these little Hondas or Toyotas or Focuses or whatever it is and run 1,000 horsepower through that thing. You talk about innovation of the hot-rodders in the '30s -- it's nothing compared with what thousands of these kids are able to do today."

Shelby reminisced fondly about his experiences. He can tell you how he broke land speed records at Bonneville in 1954 for Austin-Healey and won the 1959 24-Hours of LeMans with co-driver Ray Salvadori in their Aston Martin DBR1/300. He can talk about the time in November 1954 that during the Carrera Pan Americana Mexico he T-boned a large rock near Oaxaca and flipped his Austin-Healey four times. Indians found him and supplied him with strong drinks to ease the pain of his broken bones, cuts, bruises and a shattered elbow. And he can tell of the following March, when he took a break from his surgeries to repair that damage and teamed with Phil Hill to co-drive a 3.0-liter Monza Ferrari at Sebring.

He can chronicle his transition from driver to designer: "I always wanted to build my own car. And by studying, by living at Ferrari, Maserati and Aston Martin and all the little factories in Europe I decided I wanted to." He can say how he turned the image of Dodge around back in 1990 and give you the skinny on Lee Iacocca: "Most people think Iacocca is a soap salesman, but he's really a trained engineer. His strength is finance, so he wouldn't give us money to go build a sport car. Finally Bob Lutz and I got together and I said, 'I will tell Iacocca that it doesn't cost much money to build it.' And we'll take that V-10 engine and build 318 and it wasn't worth a hoot. By the time we were $40-50 million in, it was too late to cut it off. So that's where the Viper came from."

He remembers all the details of the Cobra program. "I never realized that when we started building those Cobras that they would amount to what they did. All I was trying to do was hustle enough money together to build a hundred of them," Shelby said. "Lee Iacocca gave me that money, $25,000. I told him if he would get me $25,000, that I could build a car that would blow the Corvettes off. And we did that, built 100 of them. Started winning races. I built 1,000 Cobras. I went out of business because emissions and safety [regulations] were coming along. Performance went away as far as sports cars and production cars after the muscle-car era. After we finished building the Mustang, I figured it was over. So I went to Africa." He recalls building the Daytona coupe: "We went over and beat the Ferraris for the world championship. Still the only American car that ever did it." He could chat about the Viper and how he helped introduce the concept coupe at the 1992 at the Los Angeles Auto Show.

But Shelby just couldn't bring himself to compare this racing spectacle with any other or this era with another, including the future. "It's kind of like asking me to compare [Juan Manuel] Fangio and [Michael] Schumacher," he said. "You have things that happen in every era, like the muscle cars in the '60s. They say that was the glory days of American automobiles. But now the same-sized engines in the 1970s put out a big V8 -- they put out 100 horsepower -- now they've got 'em putting out 500-600 horsepower. That's what electronics have done. That's progression. The muscle cars today are a hell of a lot better than the muscle cars were then and we've got a lot of them. So I think every era is great -- especially as long as I'm alive to see it. So I don't compare what was best then or will the kids today carry on."

"We were hot-rodders in the '30s, '40s, '50s, '60s. Most of us didn't have an education," the longtime pal of NHRA founder Wally Parks said. "Now you have these trained engineers, kids who went school at the university, and they're 10 times smarter than we were. And just look what's happening to the automotive world. They're really doing some great things. I'm just proud these kids are doing what they're doing."

Shelby is still making an impact, including input into the Shelby Series 1 sports car program. "I don't know . . . just always been around cars and liked it," he said. "Now I'm back, working with Ford on a couple of projects. I still love cars and airplanes. I love going to work every day."

He

knows he's a fortunate man. "With a heart transplant and a kidney transplant,

I'm very lucky to be alive and be able to do all these things," he said. Shelby

never forgot where he came from and never has hesitated to help others. "When

I was waiting for a heart, a couple of kids passed away waiting for hearts .

. . close to me there in the hospital. And so I said I'd try to help them get

organs if I got one," he said. "I got one two weeks about before I was going

to croak. That was 14 years ago."

He

knows he's a fortunate man. "With a heart transplant and a kidney transplant,

I'm very lucky to be alive and be able to do all these things," he said. Shelby

never forgot where he came from and never has hesitated to help others. "When

I was waiting for a heart, a couple of kids passed away waiting for hearts .

. . close to me there in the hospital. And so I said I'd try to help them get

organs if I got one," he said. "I got one two weeks about before I was going

to croak. That was 14 years ago."

In October 1991 he created the Carroll Shelby Children's Foundation(tm), dedicated to providing financial assistance for acute coronary and kidney care for indigent children.

"I'm the luckiest guy in the world, to be here, talking to you all. And I'm just thankful not only to be here, but every day is Christmas for me."

Hollywood has treated Shelby well. "There has been a bunch of movies made about my cars over the years. I've had 15 people want to make a movie of my life," he said. "I just keep telling them it ain't over. Heh-heh-heh - I hope."

The next pair of Top Fuel cars fires up. And this man who calls every day Christmas Day snaps his attention to the Christmas tree. Only this former chicken farmer knows what visions are bouncing around in his brain. He watches them go a quarter-mile, parachutes fluttering in the crosswind.

Carroll Shelby exhales and smiles. ![]()

Copyright 1999-2004, Drag Racing Online and Racing Net Source